Understanding The Difference Between Alzheimer's, Dementia,

And Normal Age-Related Memory Loss

As the pages of the calendar turn, it's normal to notice certain shifts in our cognitive abilities. Misplacing keys, forgetting a name momentarily, or taking longer to learn new tasks—these are often just part of the aging tapestry, not immediate cause for alarm.

The Tapestry of Memory: Age, Environment, Lifestyle, Genetics

These moments, though sometimes frustrating, don't significantly impair one's ability to navigate daily life. They're gentle reminders of the passage of time, not signs of a steep decline in cognitive function.

Beyond Forgetfulness: Decoding the Stages and Signs of Cognitive Decline

However, when memory lapses become pervasive enough to disrupt daily activities—struggling to follow a familiar recipe, repeatedly asking the same questions, or getting lost in a well-known neighborhood—the narrative changes. Alzheimer's and dementia weave a different pattern, one marked by a gradual yet relentless decline in memory, language, problem-solving abilities, and the capacity to perform simple tasks. These conditions represent not just the loss of memories but the erosion of the self, as the essence of who we are is inextricably linked to our experiences, our knowledge, and how we interact with the world.

Clinical Definition of Dementia

Dementia serves as an umbrella term for a range of neurological conditions that involve a decline in cognitive functions severe enough to interfere with daily life. Unlike Alzheimer's disease, which is a specific cause of dementia characterized by particular brain changes, dementia itself is defined by symptoms rather than underlying pathology.

These symptoms include impairments in memory, communication, and thinking, as well as changes in mood and behavior. Dementia can result from various causes, including Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and fronto-temporal dementia, each with its own set of characteristics and progression patterns.

Diagnosing Dementia

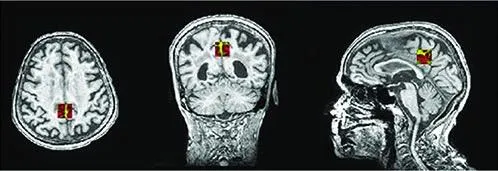

This involves a comprehensive evaluation that includes medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and often, cognitive and neuropsychological tests to assess memory, problem-solving skills, attention span, language abilities, and other aspects of mental function.

Brain imaging tests like MRI or CT scans are also commonly used to identify strokes, tumors, or other problems that could cause dementia symptoms. While diagnosing dementia can be straightforward when clear symptoms are present, determining its exact cause can be more complex, requiring specialized tests or evaluations by neurologists, geriatricians, or neuropsychologists. The diagnosis process is crucial for determining the most appropriate management strategies and support for individuals and their families.

Clinical Definition of Alzheimer's

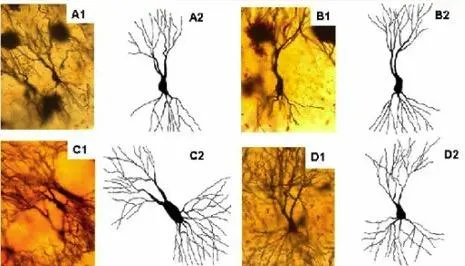

Alzheimer's disease is clinically defined as a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the deterioration of cognitive functions, primarily affecting memory, thinking skills, and the ability to perform everyday tasks.

At its core, Alzheimer's is marked by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, leading to neuronal damage and death. This accumulation is believed to disrupt cell function and communication, resulting in the symptoms associated with the disease.

Diagnosing Alzheimer's

is a multifaceted process that involves a thorough evaluation of the individual's medical history, cognitive testing, and physical examination, often complemented by neuro-imaging techniques such as MRI or CT scans to observe changes in the brain's structure. Biomarker tests measuring the levels of amyloid and tau proteins in cerebrospinal fluid can also aid in the diagnosis, offering insights into the pathological changes associated with Alzheimer's. Despite these methods, a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is frequently confirmed only through a postmortem examination of brain tissue, highlighting the complexities of diagnosing and understanding this condition.

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease progress from mild forgetfulness to severe cognitive impairments, early signs often include:

• Memory Loss:

Difficulty remembering recent events or conversations is one of the first and most common symptoms.

• Challenges in Planning or Solving Problems:

This might manifest as trouble following a familiar recipe or managing bills.

• Difficulty Completing Familiar Tasks:

People may find it hard to drive to a known location, organize a grocery list, or remember the rules of a favorite game.

• Confusion with Time or Place:

Losing track of dates, seasons, and the passage of time is common. People may forget where they are or how they got there.

• Trouble Understanding Visual Images and Spatial Relationships:

This includes difficulty reading, judging distance, and determining color or contrast, potentially causing problems with driving.

• New Problems with Words in Speaking or Writing:

People with Alzheimer's may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble following or joining a conversation, or repeat themselves.

• Misplacing Things and Losing the Ability to Retrace Steps:

They may put things in unusual places and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again, sometimes accusing others of stealing.

• Decreased or Poor Judgment:

This may be evident in dealing with money, like giving large amounts to telemarketers, or neglecting grooming and cleanliness.

• Withdrawal from Work or Social Activities:

A person with Alzheimer's might start to remove themselves from hobbies, social activities, work projects, or sports.

• Changes in Mood and Personality:

They may become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, with friends, or when out of their comfort zone.

As Alzheimer's advances to moderate and then severe stages, symptoms become more pronounced, including significant memory loss, physical difficulties, and near-total dependence on others for care.

Normal Age-Related Memory Changes

Part of the natural aging process includes some cognitive decline, and this does not necessarily indicate Alzheimer's disease or other cognitive disorders. These changes can affect memory and cognitive abilities but typically don't significantly impair daily functioning.

Here's a list of known normal age-related changes in memory:

1. Slower Processing Speed:

It might take longer to learn new information or retrieve information, including names, dates, and where items are located.

2. Occasional Forgetfulness:

Forgetting appointments or where you left things like keys or glasses from time to time.

3. Difficulty with Multitasking:

Managing multiple tasks simultaneously becomes more challenging, requiring more focus than before.

4. Trouble with Recall:

Struggling to remember a word or name during a conversation but recalling it later.

5. Decreased Attention Span:

Finding it harder to concentrate or easily getting distracted during tasks or conversations.

6. Mild Decreases in Problem-Solving Skills:

Taking more time to solve problems or make decisions based on complex information.

7. Difficulty in Learning New Skills:

Experiencing a longer learning curve when acquiring new skills or adapting to new technologies.

8. Needing More Time to Process Information:

Requiring additional time to understand complex instructions or navigate new environments.

9. Changes in Spatial Orientation and Perception:

Experiencing slight difficulties with spatial orientation, like misjudging distances or directions, which is not as pronounced as in cognitive disorders.

10. Variability in Memory Recall:

Noticing that some days are better than others in terms of memory and cognitive performance, often influenced by factors like stress, fatigue, or physical health.

It's important to differentiate these normal age-related changes from symptoms of dementia or Alzheimer's disease, which are more severe and interfere with daily life. While age-related memory changes are mild and mainly affect the speed of cognitive processes, dementia involves a significant decline in cognitive abilities, including memory, language skills, understanding, and judgment.

Potential Causes of Alzheimer's, Dementia, Memory Loss And Other Cognitive Diseases

The exact cause of Alzheimer's disease is not fully understood, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over time. Below are the potential causes and risk factors that have been identified through research:

1. Genetic Factors:

Familial Alzheimer's Disease (FAD): A rare form of Alzheimer's caused by mutations in certain genes (PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP) that is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

Risk Genes: The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, particularly the APOE ε4 allele, has been identified as a significant risk factor for the more common, late-onset form of Alzheimer's.

2. Age:

Age is the most significant known risk factor for Alzheimer's, with the risk increasing significantly after age 65.

3. Family History:

Having a parent, brother, sister, or child with Alzheimer's increases one's risk of developing the disease, suggesting genetic factors play a role.

4. Lifestyle and Heart Health:

Factors that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (e.g., lack of exercise, obesity, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, poorly controlled diabetes) are also risk factors for Alzheimer's.

5. Head Injuries:

There is some evidence to suggest that repeated head injuries or severe head trauma may increase the risk of Alzheimer's.

6. Sleep Patterns:

Poor sleep patterns, such as difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's.

7. Education, Social Engagement, and Cognitive Activity:

- Lower levels of education and less participation in mentally stimulating activities have been associated with higher risks of Alzheimer's. Social engagement and maintaining strong social networks appear to have a protective effect.

8. Other Factors:

Depression: Some studies suggest a history of depression may be linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer's. Chronic Stress: Ongoing, high levels of stress have been suggested as a possible risk factor for Alzheimer's.

Poor Diet: A diet lacking in fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids, and high in saturated fats, may increase Alzheimer's risk.

Alcohol Consumption: Excessive alcohol consumption over a long period has been associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's (more info can be found on this below).

Environmental Factors: Exposure to certain environmental factors, such as heavy metals or pesticides, has been proposed as a potential risk factor, though evidence is not conclusive.

It's clear that the precise cause of cognitive decline is complicated and difficult to pinpoint due to the disease's multifactorial nature, involving a complex interplay of genetic, biological, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Ongoing research continues to explore these relationships to better understand how Alzheimer's develops and to find effective ways to treat and prevent the disease.

The Alzheimer Alcohol Link

The link between alcohol consumption and Alzheimer's disease is a subject of ongoing research and discussion in the scientific community. Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurological disorder that leads to memory loss, cognitive decline, and ultimately, an inability to perform everyday activities.

The connection between alcohol use and Alzheimer's involves several potential mechanisms:

1. Neurotoxic Effects: Heavy alcohol consumption is known to be neurotoxic, causing damage to brain cells and leading to cognitive impairments that can resemble or exacerbate Alzheimer's disease symptoms.

2. Vitamin Deficiencies: Chronic alcohol abuse can lead to deficiencies in essential vitamins, such as vitamin B1 (thiamine), which is crucial for brain health. Such deficiencies can contribute to cognitive decline and dementia.

3. Inflammation: Alcohol can induce inflammation in the brain, which is a key factor in the development and progression of Alzheimer's disease.

4. Brain Structure Changes: Heavy drinking over a long period can lead to changes in the brain's structure, including a reduction in brain volume, which can affect cognitive functions.

5. Genetic Factors: Some studies suggest that the impact of alcohol on Alzheimer's risk may vary depending on an individual's genetic makeup, particularly in relation to genes involved in alcohol metabolism and Alzheimer's susceptibility.

It's important to note that moderate alcohol consumption has been suggested in some studies to have a protective effect against cognitive decline, though this is controversial and not universally accepted. The definition of "moderate" can vary, and the potential benefits must be weighed against the risks, including the risk of developing other health issues.

Overall, while heavy and chronic alcohol consumption is clearly linked to negative cognitive outcomes, the precise relationship between alcohol and Alzheimer's disease is complex and influenced by various factors. Moderation and individual health considerations should guide alcohol consumption decisions.

Deciphering the Stages: A Path Marked by Progression

Alzheimer's and dementia are not static; they evolve, progressing through stages that range from mild (sometimes barely noticeable) to severe (where independence is lost). In the early stages, subtle changes in cognition and behavior might be brushed off as normal aging or stress. As the disease advances, the symptoms become more pronounced—confusion, difficulty speaking and understanding, erratic behavior, and eventually, a decline in physical abilities. This progression not only affects the individual's quality of life but also poses significant challenges for caregivers and loved ones.

The Journey to Diagnosis: Piecing Together the Puzzle

Diagnosing Alzheimer's or dementia is akin to assembling a complex puzzle without having all the pieces. There's no single test that can definitively pinpoint the disease. Instead, doctors rely on a combination of medical history, physical exams, neurological assessments, and sometimes, genetic testing to make an informed diagnosis. Imaging tests like MRI and CT scans can offer insights into changes in the brain's structure, while cognitive tests assess memory, problem-solving, attention, counting, and language skills. This comprehensive approach helps distinguish between normal age-related changes and the early signs of cognitive impairment.

Navigating the Path Forward

Understanding Alzheimer's and dementia is just the beginning. It opens up avenues for support, treatment options that can manage symptoms, and strategies to improve quality of life. While there's currently no cure, advancements in research offer hope, shining a light on potential therapies and interventions that could one day alter the course of these conditions.

The journey through Alzheimer's and dementia is undeniably challenging, marked by moments of profound sadness and loss. Yet, it's also punctuated by instances of incredible resilience, deep human connection, and the enduring power of love and memory. In the face of this adversity, there's an opportunity to come together, to learn, to support, and to advocate, ensuring that those navigating this path do not walk it alone.

© 2024 TodaysHealthDiscoveries.com | All Rights Reserved

This site is not a part of Google™ website or network of sites such as Youtube™ or any company owned by Google™ or Youtube™. Additionally this website is not endorsed by Google™ Youtube™ Inc. in any way. Google™ is a trademark for all their respective companies.